There was a War Between WHERE and WHO??

When asked to think of a war on American soil one would probably say the Civil War, the Revolutionary War, maybe the War of 1812 or the French-Indian War if they’re thinking hard, or World War 2 if they’re getting technical. They probably wouldn’t jump to the Missouri-Mormon War. As the name implies, this war took place in Missouri. The war was officially in 1838 with buildup and consequences long before and after, but there was never a government’s military involved. Instead of opposing armies, it was fought between fairly regular men, both Missourian and Mormons coming from the east in search of religious freedom. While both sides have understandable motivations, the federal government undeniably failed the Mormons by failing to take a stand against their unjust treatment even when their leader went to the Capitol to ask for it. Lives of the minority were valued less than the votes of the majority and this is where the government failed. Not only would joining this war have been just but the fact that the United States didn’t is explicitly unjust.

In November of 1839 Joseph Smith and his official recorder Elias Higbee arrived in Washington DC with the goal of finding a sort of redress for what his people had just suffered. As background, the Mormons had believed that their Garden of Eden would be in Jackson County, Missouri and headed there to find it (their Prophet Joseph Smith had also been tarred and feathered in a previous location which was extra incentive). While Missouri initially seemed like a fresh start, they quickly ran into issues. By this point Missouri had been admitted to the Union as a slave state, and a new population of Northerners with largely anti-slavery views was startling to many locals. Some Missourians also believed that the Mormons were inciting Native Americans to rise up against the local government to get their land back (Kinney 103). While Smith and the people he represented tried somewhat to get along with their neighbors, these significant issues were hard to get over. An influx of any new population typically stirs up resentment from locals, and this was heightened by the vast differences in religious beliefs. When tensions heightened, Governor Lilburn Boggs permitted Missouri’s Volunteer Militia to get involved. The series of events was described the following way by Mormon historian Richard Anderson: “Executive paralysis permitted terrorism, which forced Mormons to self-defense, which was immediately labeled as an "insurrection", and was put down by the activated militia of the county.”

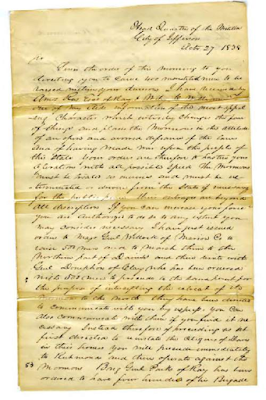

Missouri Executive Order 44, also known as the “Mormon Extermination Order” was issued by Governor Lilburn Boggs in 1838. It reads in part “The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state”. This blatantly targeted the Mormons for their membership in a religious group, something the US Constitution protects against in the 1st amendment. It does not specify if extermination is to mean killing, or driving out of state, however both would be awful to do, especially on the basis of religion. In many cases this would’ve been immediately denounced by the federal government, but Mormons had been so othered socially that there was barely any outside backlash. Three days after the order, 240 militiamen/vigilantes killed 17 members of the church. Some of them had even been killed while surrendering. None of the men responsible for the killings were ever faced with legal consequences.

This policy was a violation of the most basic rights of American citizens. The very first amendment of the Constitution guaranteed citizens the right to freedom of religion, and allowing one state to force out an entire religious group is an obvious violation of this right. The federal government was made aware of this but was ignored in the name of protecting the politicians next election cycle. The Extermination Order essentially went unchallenged, and wasn't even officially rescinded until 1976 (Pokin). When Joseph Smith went to Washington DC to ask President Martin Van Buren for help securing justice, Van Buren replied "What can I do? I can do nothing for you,–if I do anything, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri". Van Buren's objection was not that the cause was morally wrong, or that the state was in compliance with federal law, but simply that it would make his next election cycle more difficult. They pivoted to trying to bring it up to the Senate, where “They didn’t consider whether the Mormons deserved redress and reparations ... Instead the judiciary committee was tasked with determining whether or not the federal government had jurisdiction in the case” (McBride qtd. in Proctor). It was decided the federal government did not have jurisdiction, and they were told to make their case to state government.

Politicians disregarding ethics to think of electoral strategy was not new at this time, and has not stopped since. With rare exceptions, your average politician will not make a decision unless they are sure it won't make them more vulnerable the next election cycle. It is often unpopular to speak in defense of a scapegoat. It is uncomfortable to put your voice in support of a group being widely attacked. This is just the reason why many politicians prioritize saving their seat over furthering the common good. It is because of this that it is important to be critical of politicians. If they do something that seems inconsistent with the claims they ran on, ask why? If they suddenly switch positions on an issue, look into what could've changed to make that seem worth it. Holding politicians accountable is incredibly important in making sure the hypotheticals of today aren't the forgotten horrors of tomorrow.

Boggs, Lilburn. “Missouri Executive Order 44.” Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias, https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/11753408#Text_of_the_Order.

“Joseph Smith Goes to Washington, 1839-40: Religious Studies Center.” Joseph Smith Goes to Washington, 1839-40 | Religious Studies Center, https://rsc.byu.edu/joseph-smith-prophet-seer/joseph-smith-goes-washington-1839-40.

Kinney, Brandon G. Mormon War: Zion and the Missouri Extermination Order of 1838. WESTHOLME PUBLISHING, 2021.

Pokin, Steve. “Pokin around: Was There Ever a Time in Missouri When You Could Legally Kill a Mormon?” Leader, News-Leader, 2 Sept. 2018, https://www.news-leader.com/story/news/local/ozarks/2018/09/01/missouri-executive-order-44-mormon-war/1147461002/.

Proctor, Maurine. “Why Joseph Smith's Visit with Martin Van Buren Was the Most Important Trip of His Life: Meridian Magazine.” Latter, 10 Aug. 2018, https://latterdaysaintmag.com/why-joseph-smiths-visit-with-martin-van-buren-was-the-most-important-trip-of-his-life/.

Comments

Post a Comment